Patterns in the Sky...Patterns in the Rain...

There is a lot of information available about Climate Change so I'm going to limit what I post here to articles that also relate Climate Change to some of the other issues I explore in these pages, like Scalar Weapons, Chemtrails and Peak Oil. If Scalar and 'weather modification' weapons are indeed out there and operational it is not unreasonable to link these devices to the current global issues of Climate Change and erratic and severe weather patterns. Also some would have it that Chemtrails are a secret project to mitigate against Climate Change and others go so far as to state that Climate Change is a solar system wide phenomena which the 'powers that be' are aware of and acting on.

Make your own mind up after reviewing the data, but what is not in doubt (except by those who remain in total denial) is that Climate Change is happening now and rapidly getting worse.

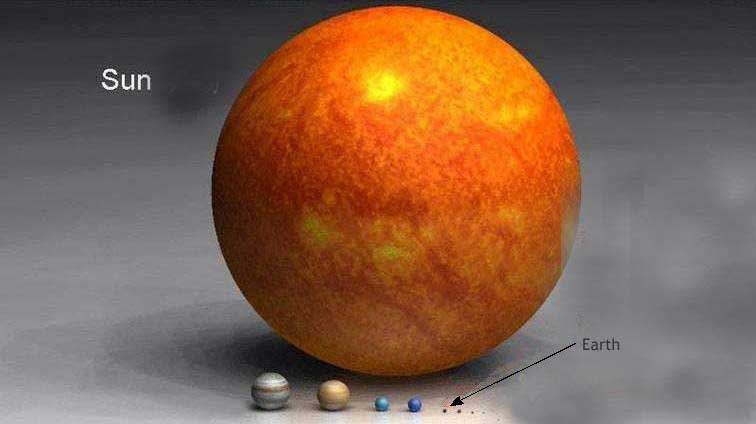

Could it be the Sun? - all other excuses could be just that, convenient excuses to help the powers that be sustain a capitalist consumer society and get us all 'carbon trading' and ever more firmly under their thumbs, when the reality is that Climate Change is way beyond our control as it is being caused by the Sun!

Perhaps we have reached the 'Tipping Point' of no return in regard to our global climate and we have no choice but to prepare and adapt. The articles below give a good general overview:

Global

warming, in capsule form

David Roberts, Gristmill

http://gristmill.grist.org/story/2005/10/18/16151/159

In accordance with Title 17

U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without

profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for research and

educational purposes.

In the midst of a long post

on Montana Gov.

Brian Schweitzer's coal-to-liquid-fuel

plans,

Oil Drummer Stuart Staniford provides a handy

one-paragraph-long roundup of evidence on global warming.

The next time someone you know asks about it, just cut and

paste this paragraph and send it to them. Warming cliff

notes!

[W]e

are reaching the point where we can see that we are

starting to make massive, probably irreversible, changes to

our climate. The glaciers are

in full retreat almost everywhere, the

Arctic is

melting (with total melting of the

summer sea ice possible, though not certain,

as early as

2020),

the permafrost is

melting,

and releasing large amounts of methane, which is a

very powerful

global warming gas, while in the last thirty

years, droughts have

doubled due to warming, hurricanes

are much more

intense all over the globe, and are showing up in places

they never did

before in recorded history. Scientists have been

projecting

changes in ocean circulation, and lo-and-behold,

they are

starting to show up, including changes to

the North Atlantic Circulation, although major change here

was previously

thought unlikely this century. There is some possibility of

changes in deepwater circulation destabilizing

methane hydrates in the ocean, particularly in

South East

Asian deeps. Oh, and the Greenland ice sheet

is now melting much

faster than climatologists expected, and the West Antarctic ice

sheet is starting to

collapse, though again,

this was

previously thought unlikely. Also paleoclimatological

studies have made it clear that in the past the

climate abruptly

flipped between modes, sometimes with dramatic

change in as little as

three years. And we are making

rapid changes

in carbon dioxide, known to be critically

important in regulating the temperature of this sensitive

climatic system for a century

now.

As he says, "maybe there's some scientific doubt still on

any individual piece of the picture, but the gestalt is

starting to look extremely alarming."

Yes.

This page will highlight current news stories and

information on Climate Change from a variety of sources,

starting here with a couple of recent articles in the

mainstream media. Firstly from the Independent newspaper in

the UK

"some

of the more spectacular solutions proposed, such as melting

the Arctic ice cap by covering it with black soot or

diverting arctic rivers.."

The Cooling World

By Peter Gwynne

There are ominous signs that the Earth’s

weather patterns have begun to change dramatically and that

these changes may portend a drastic decline in food

production — with serious political implications for just

about every nation on Earth. The drop in food output could

begin quite soon, perhaps only 10 years from now. The

regions destined to feel its impact are the great

wheat-producing lands of Canada and the U.S.S.R. in the

North, along with a number of marginally self-sufficient

tropical areas — parts of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh,

Indochina and Indonesia — where the growing season is

dependent upon the rains brought by the

monsoon.

The evidence in support of these predictions

has now begun to accumulate so massively that

meteorologists are hard-pressed to keep up with it. In

England, farmers have seen their growing season decline by

about two weeks since 1950, with a resultant overall loss

in grain production estimated at up to 100,000 tons

annually.

During the same time, the average temperature

around the equator has risen by a fraction of a degree — a

fraction that in some areas can mean drought and

desolation. Last April, in the most devastating outbreak of

tornadoes ever recorded, 148 twisters killed more than 300

people and caused half a billion dollars’ worth of damage

in 13 U.S. states.

To scientists, these seemingly disparate

incidents represent the advance signs of fundamental

changes in the world’s weather. Meteorologists disagree

about the cause and extent of the trend, as well as over

its specific impact on local weather conditions. But they

are almost unanimous in the view that the trend will reduce

agricultural productivity for the rest of the century. If

the climatic change is as profound as some of the

pessimists fear, the resulting famines could be

catastrophic.

“A major climatic change would force economic

and social adjustments on a worldwide scale,” warns a

recent report by the National Academy of Sciences, “because

the global patterns of food production and population that

have evolved are implicitly dependent on the climate of the

present century.”

A survey completed last year by Dr. Murray

Mitchell of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration reveals a drop of half a degree in average

ground temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere between 1945

and 1968. According to George Kukla of Columbia University,

satellite photos indicated a sudden, large increase in

Northern Hemisphere snow cover in the winter of 1971-72.

And a study released last month by two NOAA scientists

notes that the amount of sunshine reaching the ground in

the continental U.S. diminished by 1.3% between 1964 and

1972.

To the layman, the relatively small changes

in temperature and sunshine can be highly misleading. Reid

Bryson of the University of Wisconsin points out that the

Earth’s average temperature during the great Ice Ages was

only about seven degrees lower than during its warmest eras

— and that the present decline has taken the planet about a

sixth of the way toward the Ice Age

average.

Others regard the cooling as a reversion to

the “little ice age” conditions that brought bitter winters

to much of Europe and northern America between 1600 and

1900 — years when the Thames used to freeze so solidly that

Londoners roasted oxen on the ice and when iceboats sailed

the Hudson River almost as far south as New York

City.

Just what causes the onset of major and minor

ice ages remains a mystery. “Our knowledge of the

mechanisms of climatic change is at least as fragmentary as

our data,” concedes the National Academy of Sciences

report. “Not only are the basic scientific questions

largely unanswered, but in many cases we do not yet know

enough to pose the key questions.”

Meteorologists think that they can forecast

the short-term results of the return to the norm of the

last century. They begin by noting the slight drop in

overall temperature that produces large numbers of pressure

centers in the upper atmosphere. These break up the smooth

flow of westerly winds over temperate areas. The stagnant

air produced in this way causes an increase in extremes of

local weather such as droughts, floods, extended dry

spells, long freezes, delayed monsoons and even local

temperature increases — all of which have a direct impact

on food supplies.

“The world’s food-producing system,” warns

Dr. James D. McQuigg of NOAA’s Center for Climatic and

Environmental Assessment, “is much more sensitive to the

weather variable than it was even five years

ago.”

Furthermore, the growth of world population

and creation of new national boundaries make it impossible

for starving peoples to migrate from their devastated

fields, as they did during past famines.

Climatologists are pessimistic that political

leaders will take any positive action to compensate for the

climatic change, or even to allay its

effects.

They concede that some of the more

spectacular solutions proposed, such as melting the Arctic

ice cap by covering it with black soot or diverting arctic

rivers, might create problems far greater than those they

solve. But the scientists see few signs that government

leaders anywhere are even prepared to take the simple

measures of stockpiling food or of introducing the

variables of climatic uncertainty into economic projections

of future food supplies. The longer the planners delay, the

more difficult will they find it to cope with climatic

change once the results become grim

reality.

Newsweek’s 1975 Article About

The Coming Ice Age

http://sweetness-light.com/archive/newsweeks-1975-article-about-the-coming-ice-age

"Earth" (noun) - from ancient

Alien language, meaning 'Planet of

Idiots'

http://news.independent.co.uk/world/environment/article316604.ece

Melting

Planet

Species

are dying out faster than we have dared recognise,

scientists will warn this week. The erosion of polar ice is

the first break in a fragile chain of life extending across

the planet, from bears in the north to penguins in the far

south

By Andrew

Buncombe in Anchorage and Severin Carrell in London

Published: 02 October 2005

The

polar bear is one of the natural world's most famous

predators - the king of the Arctic wastelands. But, like

its vast Arctic home, the polar bear is under unprecedented

threat. Both are disappearing with alarming speed.

Thinning ice and longer summers are destroying the bears'

habitat, and as the ice floes shrink, the desperate animals

are driven by starvation into human settlements - to be

shot. Stranded polar bears are drowning in large numbers as

they try to swim hundreds of miles to find increasingly

scarce ice floes. Local hunters find their corpses floating

on seas once coated in a thick skin of ice.

It is a phenomenon that frightens the native people that

live around the Arctic. Many fear their children will never

know the polar bear. "The ice is moving further and further

north," said Charlie Johnson, 64, an Alaskan Nupiak from

Nome, in the state's far west. "In the Bering Sea the ice

leaves earlier and earlier. On the north slope, the ice is

retreating as far as 300 or 400 miles offshore."

Last year, hunters found half a dozen bears that had

drowned about 200 miles north of Barrow, on Alaska's

northern coast. "It seems they had tried to swim for shore

... A polar bear might be able to swim 100 miles but not

400."

His alarming testimony, given at a conference on global

warming and native communities held in the Alaskan capital,

Anchorage, last week, is just one story of the many changes

happening across the globe. Climate change threatens the

survival of thousands of species - a threat unparalleled

since the last ice age, which ended some 10,000 years ago.

The vast majority, scientists will warn this week, are

migratory animals - sperm whales, polar bears, gazelles,

garden birds and turtles - whose survival depends on the

intricate web of habitats, food supplies and weather

conditions which, for some species, can stretch for 6,500

miles. Every link of that chain is slowly but perceptibly

altering.

Europe's most senior ecologists and conservationists are

meeting in Aviemore, in the Scottish Highlands, this week

for a conference on the impact of climate change on

migratory species, an event organised by the British

government as part of its presidency of the European Union.

It is a well-chosen location. Aviemore's major winter

employer - skiing - is a victim of warmer winters. Ski

slopes in the Cairngorms, which once had snow caps year

round on the highest peaks, have recently been closed down

when the winter snow failed. The snow bunting, ptarmigan

and dotterel - some of Scotland's rarest birds - are also

given little chance of survival as their harsh and marginal

winter environments disappear.

A report being presented this week in Aviemore reveals this

is a pattern being repeated around the world. In the

sub-Arctic tundra,caribou are threatened by "multiple

climate change impacts". Deeper snow at higher latitudes

makes it harder for caribou herds to travel. Faster and

more regular "freeze-thaw" cycles make it harder to dig out

food under thick crusts of ice-covered snow. Wetter and

warmer winters are cutting calving success, and increasing

insect attacks and disease.

The same holds true for migratory wading birds such as the

red knot and the northern seal. The endangered spoon-billed

sandpiper, too, faces extinction, the report says. They are

of "key concern". It says that species "cannot shift

further north as their climates become warmer. They have

nowhere left to go ... We can see, very clearly, that most

migratory species are drifting towards the poles."

The report, passed to The Independent on Sunday, and

commissioned by the Department for the Environment, Food

and Rural Affairs (Defra), makes gloomy predictions about

the world's animal populations. "The habitats of migratory

species most vulnerable to climate change were found to be

tundra, cloud forest, sea ice and low-lying coastal areas,"

it states. "Increased droughts and lowered water tables,

particularly in key areas used as 'staging posts' on

migration, were also identified as key threats stemming

from climate change."

Some of itsfindings include:

* Four out of five migratory birds listed by the UN face

problems ranging from lower water tables to increased

droughts, spreading deserts and shifting food supplies in

their crucial "fuelling stations" as they migrate.

* One-third of turtle nesting sites in the Caribbean - home

to diminishing numbers of green, hawksbill and loggerhead

turtles - would be swamped by a sea level rise of 50cm

(20ins). This will "drastically" hit their numbers. At the

same time, shallow waters used by the endangered

Mediterranean monk seal, dolphins, dugongs and manatees

will slowly disappear.

* Whales, salmon, cod, penguins and kittiwakes are affected

by shifts in distribution and abundance of krill and

plankton, which has "declined in places to a hundredth or

thousandth of former numbers because of warmer sea-surface

temperatures."

* Increased dam building, a response to water shortages and

growing demand, is affecting the natural migration patterns

of tucuxi, South American river dolphins, "with potentially

damaging results".

* Fewer chiffchaffs, blackbirds, robins and song thrushes

are migrating from the UK due to warmer winters. Egg-laying

is also getting two to three weeks earlier than 30 years

ago, showing a change in the birds' biological clocks.

The science magazine Nature predicted last year that up to

37 per cent of terrestrial species could become extinct by

2050. And the Defra report presents more problems than

solutions. Tackling these crises will be far more

complicated than just building more nature reserves - a

problem that Jim Knight, the nature conservation minister,

acknowledges.

A key issue in sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, is

profound poverty. After visiting the Democratic Republic of

the Congo last month, Mr Knight found it difficult to

condemn local people eating gorillas, already endangered.

"You can't blame an individual who doesn't know how they're

going to feed their family every day from harvesting what's

around them. That's a real challenge," he said.

And the clash between nature and human need - a critical

issue across Africa - is likely to worsen. As its savannah

and forests begin shifting south, migratory animals will

shift along with them. Some of the continent's major

national parks and reserves - such as the Masai-Mara or

Serengeti - may also have to move their boundaries if their

game species, the elephant and wildebeest, are to be

properly protected. This will bring conflict with local

communities.

There is also a gap in scientific knowledge between what

has been discovered about the impact of climate change in

the industrialised world and in less developed countries.

Similarly, fisheries experts know more about species such

as cod and haddock, than they do about fish humans don't

eat.

Many environmentalists are pessimistic about the prospects

of halting, let alone reversing, this trend. "Are we

fighting a losing battle? Yes, we probably are," one

naturalist told the IoS last month.

The UK, which is attempting to put climate change at the

top of the global agenda during its presidency of the G8

group of industrialised nations, is still struggling to

persuade the American, Japanese and Australian governments

to admit that mankind's gas emissions are the biggest

threat. These three continue to insist there is no proof

that climate change is largely manmade.

And many British environmentalists suspect that Tony

Blair's public commitment to a tougher global treaty to

replace the Kyoto Protocol, aimed at a 60 per cent cut in

carbon dioxide emissions by 2050, is not being backed up by

the Government in private.

Despite President George Bush's resistance to a new global

climate treaty, many US states are being far more radical.

Even the G8 communiqué after the Gleneagles summit in July

had Mr Bush confirming that the climate was warming.

In Alaska last week, satellite images released by two US

universities and the space agency Nasa revealed that the

amount of sea-ice cover over the polar ice cap has fallen

for the past four years. "A long-term decline is under

way," said Walt Meier of the National Snow and Ice Data

Centre.

The Arctic's native communities don't need satellite images

to tell them this. John Keogak, 47, an Inuvialuit from

Canada's North-West Territories, hunts polar bears, seals,

caribou and musk ox. "The polar bear is part of our

culture," he said. "They use the ice as a hunting ground

for the seals. If there is no ice there is no way the bears

will be able to catch the seals." He said the number of

bears was decreasing and feared his children might not be

able to hunt them. He said: "There is an earlier break-up

of ice, a later freeze-up. Now it's more rapid. Something

is happening."

And now, said Mr Keogak, there was evidence that polar

bears are facing an unusual competitor - the grizzly bear.

As the sub-Arctic tundra and wastelands thaw, the grizzly

is moving north, colonising areas where they were

previously unable to survive. Life for Alaska's polar bears

is rapidly becoming very precarious.

Vanishing

from the earth

Mountain

gorilla

Already listed as "critically endangered", only about 700

mountain gorillas, including the distinctively marked adult

male silverbacks, migrate within the cloud forests of the

volcanic Virunga mountains of the Democratic Republic of

the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda. After a century of human

persecution it faced extinction. Now its unique but

marginal mountain forests - already heavily reduced by

forestry - are shrinking, because of climate change. It

will be forced to climb higher for cooler climates, but

will effectively run out of mountain.

Across Africa, habitats are shifting as temperatures rise,

or disappearing in droughts, affecting the migrations of

millions of wildebeest, and savannah elephant and Thomson's

gazelle. This will hit game reserves and national parks -

forcing many to move their boundaries.

Green

turtle

The number of male green turtles is falling because of

rising temperatures, threatening their survival. Turtle

nests need a temperature of precisely 28.8C to hatch even

numbers of males and females. On Ascension Island, where

nest temperatures are up 0.5C,females now outnumber males

three to one. On Antigua too, nest temperatures for

hawkbill turtles are higher than the ideal incubation

level. Hatchling survival rates are also cut by higher

temperatures. Egg-laying beaches for all species of turtle

are being lost to rising sea levels. A third of nesting

beaches in the Caribbean would be lost by a 50cm rise in

sea level.

Saiga

antelope

This rare antelope, thought to be half-way between an

antelope and a sheep, and found in Russia and Mongolia, is

"critically endangered". Hunted heavily, its autumn

migration to escape bitter weather and spring migration to

find water and food are being hit by unusual weather

cycles. The antelope will be forced by climate instability

to find new grazing areas, coming intoconflict with humans.

Bad years can cut its numbers by 50 per cent, because of

high mortality and poor birth rates.

Sperm

whale

The migration of the sperm whale, one of the earth's

largest mammals, made famous by Herman Melville's

epic

Moby-Dick,

is closely linked to the squid, its main food source. Squid

numbers are affected by warmer water and weather phenomena

such as El Niño. Adult male sperm whales up to 20m long

like cold water in the disappearing ice-packs. Warm water

cuts sperm whale reproduction because food supplies fall.

Around the Galapagos Islands, a fall in births is linked to

higher sea surface temperatures. Plankton and krill, key

foods for many cetaceans such as the pilot whale, have in

some regions declined 100-fold in warmer water.

AND ONE FROM THE NEW YORK

TIMES

AND ONE FROM THE NEW YORK

TIMES

Arctic Could

Be Ice-Free By Century's End... 500,000 Extra Square Miles

Melted This Year

In

a Melting Trend, Less Arctic Ice to Go Around

The New York Times

September

29, 2005

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/29/science/29ice.html?ex=1285646400&

en=7b3487fa5bc2d915&ei=5090&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss

In accordance with Title 17

U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without

profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for research and

educational purposes.

The floating cap of sea ice on

the Arctic Ocean shrank this summer to what is probably its

smallest size in at least a century of record keeping,

continuing a trend toward less summer ice, a team of

climate experts reported yesterday.

That shift is hard to explain without attributing it in

part to human-caused global warming, the team's members and

other experts on the region said.

The change also appears to be headed toward becoming

self-sustaining: the increased open water absorbs solar

energy that would otherwise be reflected back into space by

bright white ice, said Ted A. Scambos, a scientist at the

National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo., which

compiled the data along with the National Aeronautics and

Space Administration.

"Feedbacks in the system are starting to take hold," Dr.

Scambos said.

The data was released on the center's Web site,

www.nsidc.org.

The findings are consistent with recent computer

simulations showing that a buildup of smokestack and

tailpipe emissions of greenhouse gases could lead to a

profoundly transformed Arctic later this century, when much

of the once ice-locked ocean would routinely become open

water in summers.

Expanding areas of open water in the summer could be a boon

to whales and cod stocks, and the ice retreat could create

summertime shipping shortcuts between the Atlantic and the

Pacific.

But a host of troubles lie ahead as well. One of the most

important consequences of Arctic warming will be increased

flows of meltwater and icebergs from glaciers and ice

sheets, and thus an accelerated rise in sea levels,

threatening coastal areas. The loss of sea ice could also

hurt both polar bears and Eskimo seal hunters.

The Arctic ice cap always grows in the winter and shrinks

in the summer. The average minimum area from 1979, when

precise satellite mapping began, until 2000 was 2.69

million square miles, similar in size to the contiguous

area of the United States. The new summer low, measured on

Sept. 19, was 20 percent below that.

Before 1979, scientists estimated the size of the ice cap

based on reports from ships and airplanes.

The difference between the average ice area and the area

that persisted this summer was about 500,000 square miles,

an area about twice the size of Texas, the scientists said.

This summer was the fourth in a row with the ice cap areas

sharply below the long-term average, said Mark C. Serreze,

a senior scientist at the snow and ice center and a

professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Dr. Scambos said the consecutive reductions in the ice cap

"make it pretty certain a long-term decline is under way."

A natural cycle in the polar atmosphere called the Arctic

oscillation, which contributed to the reduction in Arctic

ice in the past, did not appear to be a factor in the past

several years, Dr. Serreze said.

He said the role of accumulating greenhouse gas emissions

had become increasingly apparent with rising air and sea

temperatures. Still, many scientists say it is not yet

possible to determine what portion of Arctic change is

being caused by rising levels of carbon dioxide and other

emissions from human sources and how much is just climate's

usual wiggles.

Dr. Serreze and other scientists said that more variability

could lie ahead and that the area of sea ice could actually

increase some years. But the scientists have found few

hints that other factors, like more Arctic cloudiness in a

warming world, will reverse the trend.

"With all that dark open water, you start to see an

increase in Arctic Ocean heat storage," Dr. Serreze said.

"Come autumn and winter that makes it a lot harder to grow

ice, and the next spring you're left with less and thinner

ice. And it's easier to lose even more the next year."

The result, he said, is that the Arctic is "becoming a

profoundly different place than we grew up thinking about."

Other experts on Arctic ice and climate disagreed on

details. For example, Ignatius G. Rigor at the University

of Washington said the change was probably linked to a mix

of factors, including influences of the atmospheric cycle.

But he agreed with Dr. Serreze that the influence from

greenhouse gases had to be involved.

"The global warming idea has to be a good part of the

story," Dr. Rigor said. "I think we have a different

climate state in the Arctic now. All of these feedbacks are

starting to kick in and really snuffing the ice out by the

end of summer."

Other experts expressed some caution. Claire L. Parkinson,

a sea ice expert at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in

Greenbelt, Md., said a host of changes in the Arctic -

including rising temperatures, melting permafrost and

shrinking sea ice - were consistent with human-caused

warming. But she emphasized that the complicated system was

still far from completely understood.

William L. Chapman, a sea ice researcher at the University

of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, said it was important to keep

in mind that the size of the ice cap could vary

tremendously, in part because of changes in wind patterns,

which can cause the ice to heap up against one Arctic shore

or drift away from another.

Water crisis

looms as Himalayan glaciers melt

NEW DELHI,

India (Reuters) -- Imagine a world without drinking

water

CNN

http://www.cnn.com/2005/TECH/science/09/09/himalayan.glaciers.reut/index.html

In accordance with Title 17

U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without

profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for research and

educational purposes.

It's a scary thought, but

scientists say the 40 percent of humanity living in South

Asia and China could well be living with little drinking

water within 50 years as global warming melts Himalayan

glaciers, the region's main water

source.

The glaciers

supply 303.6 million cubic feet every year to Asian rivers,

including the Yangtze and Yellow rivers in China, the Ganga

in India, the Indus in Pakistan, the Brahmaputra in

Bangladesh and Burma's Irrawaddy.

But as global warming increases, the glaciers have been

rapidly retreating, with average temperatures in the

Himalayas up 1 degree Celsius since the 1970s.

A World Wide Fund report published in March said a quarter

of the world's glaciers could disappear by 2050 and half by

2100.

"If

the current scenario continues, there will be very little

water left in the Ganga and its tributaries," Prakash Rao,

climate change and energy program coordinator with the fund

in India told Reuters.

"The

situation here is more critical because here they depend on

glaciers for drinking water while in other areas there are

other sources of drinking water, not just

glacial."

Experts

are alarmed.

About 67 percent of the nearly 12,124 square miles of

Himalayan glaciers are receding and in the long run as the

ice diminishes, glacial runoffs in summer and river flows

will also go down, leading to severe water shortages in the

region.

The Gangotri glacier, the source of the Ganga, India's

holiest river, is retreating 75 feet a year. And the Khumbu

Glacier in Nepal, where Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay

began their ascent of Everest, has lost more than 3 miles

since they climbed the mountain in 1953.

"The

cry in the mountains is that water has gone down and

springs have dried up," Jagdish Bahadur, an expert on

Himalayan glaciers.

"Global

climate change has had an effect, but water has also dried

up because agriculture in the mountains has increased," he

said.

In

Nepal, there are more than 3,000 glaciers that work as

reservoirs for fresh water and another 2,000 glacial lakes.

Experts estimate numerous rivers originating in Nepal's

mountains contribute about 70 percent to the pre-monsoon

flow of the Ganges that snakes through neighboring India

and Bangladesh.

"The

glaciers are shrinking due to global warming posing a risk

to water availability not only in Nepal but also in parts

of South Asia," said Arun Bhakta Shrestha, an expert on

Himalayan glaciers at the government Hydrology and

Meteorology Department.

"But

how soon or to what extent this problem will arise is

difficult to say now."

Tulsi

Maya, a farmer on the outskirts of Kathmandu, has never

heard of global warming or its impact on the rivers in the

Himalayan kingdom, but she does know that the flow of water

has gone down.

"It

used to overflow its banks and spill into the fields," the

85-year-old farmer said standing in her emerald green rice

field as she looked at the Bishnumati river, which has

ceased to be a reliable source of drinking water and

irrigation.

"Maybe

God is unkind and sends less water in the river. The flow

of water is decreasing every year," she said standing by

her grandson, Milan Dangol, who weeds the

crop.

In

the Indian Himalayas, there are already signs of water

shortages in the summer: Tourists in the rugged mountains

of Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh have to carry buckets of

water while trekkers say temperatures are much warmer than

a decade ago.

The effect can also be seen in the rest of the country.

During the summer, thousands of people in India's villages

trek for miles in search of water and even in cities water

is a precious commodity, sometimes leading to street

fights.

Indian scientists studying Himalayan glaciers fear an acute

shortage of natural drinking water in Himachal Pradesh

state based on studies of the Beas and Baspa basins from

1962 to 2001.

Two scientists from India's Space and Research Organization

using remote sensing satellites found a 23 percent drop in

glacial water in 19 of 30 glaciers mapped in the region.

Already, the impact of climate change is evident in the

soaring summer temperatures in South Asia, which go up to

122 degrees Fahrenheit, and the erratic nature of the

monsoon, one of the world's most widely watched phenomena.

"Our

research indicates the economy of the region may be

affected due to these conditions and investigations suggest

that all glaciers are reducing which could create an acute

scarcity of water," said Anil Kulkarni, who headed the team

studying the Himachal Pradesh glaciers.

Copyright

2005

Reuters. All rights

reserved.This material may not be published, broadcast,

rewritten, or redistributed.